Calculating Uncertainties on Strong-Line Abundances

How to use the Moustakas Method

Background - Strong Line Abundances

When determining the oxygen abundance of an HII region or a star-forming galaxy as a whole, the most direct and physically motivated method is to measure the electron temperature (

Strong-line abundance calibrations essentially relate the oxygen abundance to one or more line ratios involving the strongest recombination and collisionally excited (forbidden) lines (e.g., [OII]

Over the last four decades, numerous strong-line calibrations have been developed, but in general they fall into one of three categories: semi-empirical, empirical, and theoretical. The older, semi-empirical calibrations were generally tied to electron temperature measurements at low metallicites and photoionization models at high metallicities (e.g., Alloin et al. 1979; Edmunds & Pagel 1984; Dopita & Evans 1986). These hybrid calibrations were born from the observational difficulty of measuring the electron temperature of metal-rich HII regions. In contrast, the empirical methods are calibrated against high-quality observations of individual HII regions with measured direct (i.e.,

The individual problems with these various calibrations is compounded by the fact that there exist large, poorly understood systematic discrepancies, in the sense that empirical calibrations generally yield oxygen abundances that are factors of 1.5-5 lower than abundances derived using theoretical calibrations (Kewley & Ellison 2008). Unfortunately, the physical origin of this systematic discrepancy remains unsolved.

Some of the more common strong-line calibrations rely on the metallicity-sensitive

The advantage of

An additional complication is that the relation between

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from astropy.table import Table

from astropy.io import fits

from scipy.stats import norm

%matplotlib inline

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 14, 'xtick.minor.visible':True,

'ytick.minor.visible':True})

np.random.seed(5749)

def mcgaugh91_up(logR23,logO32):

return 12 - 2.939 - 0.2*logR23 - 0.237*logR23**2 - 0.305*logR23**3 - 0.0283*logR23**4 - logO32*(0.0047 - 0.0221*logR23 - 0.102*logR23**2 - 0.0817*logR23**3 - 0.00717*logR23**4)

def mcgaugh91_dw(logR23,logO32):

return 12 - 4.944 + 0.767*logR23 + 0.602*logR23**2 - logO32*(0.29 + 0.332*logR23 - 0.331*logR23**2)

fig1 = plt.figure(figsize=(8,6), constrained_layout=True)

ax1 = plt.subplot(111)

O32_vals = [-.5, 0, 0.5]

R23_vals = np.arange(-1.0,1.5,0.01)

z_vals = np.arange(6.5,9.5,0.01)

for j,ls in zip(O32_vals,['-','--','-.']):

idx = np.argwhere(np.diff(np.sign(mcgaugh91_up(R23_vals,j) - mcgaugh91_dw(R23_vals,j)))).flatten()

ax1.plot(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]], mcgaugh91_up(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]],j), 'k', ls=ls)

ax1.plot(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]], mcgaugh91_dw(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]],j), 'k', ls=ls)

ax1.set_xlabel(r'$\log(R_{23})$')

ax1.set_ylabel(r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{O}/\mathrm{H})$')

ax1.set_xlim(-1.0,1.5)

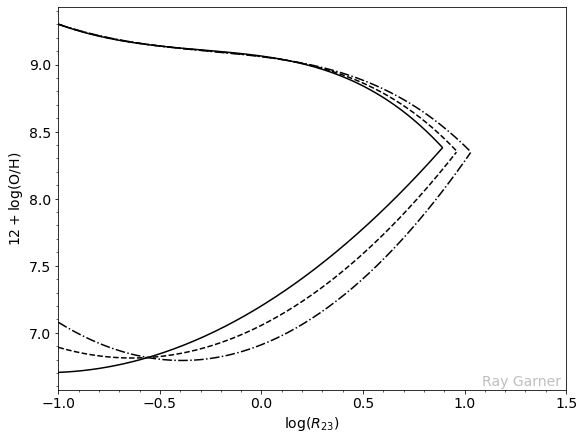

In the above figure, we have the

and this characterizes the hardness of the ionizing radiation field; the styled lines indicate different blanket values of this O32 parameter. However, we can see the broader issue. Metal-rich objects lie on the upper

Because the

Here, I am going to illustrate and provide example code for utilizing the method outlined in Moustakas et al. (2010) to determine the oxygen abundance of star-forming regions in the spiral galaxy M101 and their associated uncertainties.

Background - Monte Carlo

I will refer any interested reader to the detailed example provided by Will Clarkson at the University of Michigan, which you can read by clicking here. However, I will summarize a few brief points.

One of the most important pieces of model-fitting is to determine the “uncertainty” in the value of some parameter in the model. You might have fit some value of your model parameter to data, and it may even go through most of the datapoints and be consistent with your prior expectation on the parameter values. But unless you know what range of values of this parameter are consistent with the data, you really don’t know if your model fits at all.

First, a note and some assumptions.

It is common in the literature to condense the information contained in the deviations from the “best-fit” value to report the “1-sigma” range, often reported as

I will additionally make the same assumptions that Will Clarkson made, namely that

- our model

- any deviations between the perfect underlying pattern predicted by

If we were to conduct a large number of identical experiments, then the “true” parameters of our model

Since we cannot do an infinite number of repeat experiments, we need another way to predict what range of parameter values would be returned if we could do them. One way is the formal error-estimate: if the measurement errors all follow the same distribution, and if they are “small enough,” then you can use standard error propagation to take the measurement error and propagate it through to get a formal prediction on the error of the parameter. But there’s no guarantee that this will work in all cases. What you need in the real world is a method that will empirically find the range of parameters that fit the model to some level of “confidence” without actually doing ten thousand re-runs of the experiment to determine this range.

This is what Monte Carlo does in this context: simulate a large number of fake datasets and find the best-fit parameters using exactly the same method that you’re using to fit your real data. The range of returned parameters under these fake experiments is then a reasonable approximation to the true underlying error in the best-fit parameters.

An Example with Real Data

I have at my disposal emission line data for M101 taken from narrowband images of the M101 Group targeting the emission lines of H

Here, the data has been fully cleaned: Galactic extinction and interstellar reddening have been corrected, and line emission has been corrected for stellar Balmer absorption and contamination from [NII]

First, we load in the data, calculate the

hdul = fits.open('M101_HII_regions_corrected_photometry.fits.gz')

M101Data = Table(hdul[1].data)

M101Data['R23'] = (M101Data['O2_nored'] + M101Data['O3_nored'])/M101Data['Hb_nored']

M101Data['R23_err'] = np.abs(M101Data['R23'])*np.sqrt((np.sqrt(M101Data['O3_nored_err']**2 + M101Data['O2_nored_err']**2)/(M101Data['O2_nored']+M101Data['O3_nored']))**2 + (M101Data['Hb_nored_err']/M101Data['Hb_nored'])**2)

M101Data['O32'] = M101Data['O3_nored']/M101Data['O2_nored']

M101Data['O32_err'] = np.abs(M101Data['O32'])*np.sqrt((M101Data['O3_nored_err']/M101Data['O3_nored'])**2 + (M101Data['O2_nored_err']/M101Data['O2_nored'])**2)

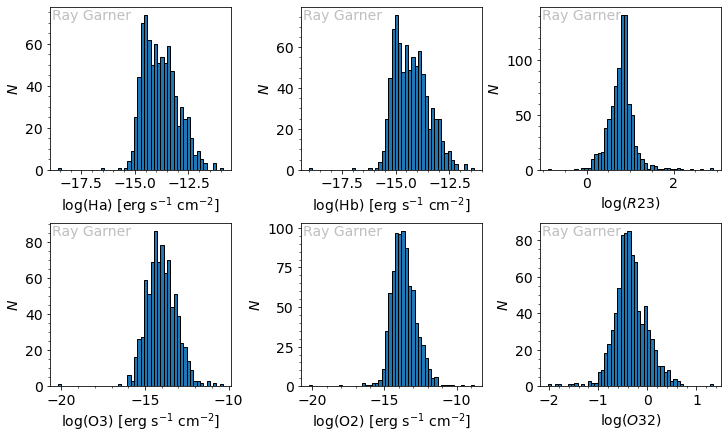

Let’s take a look at the distribution of the data:

fig2 = plt.figure(figsize=(10,6), constrained_layout=True)

ax2 = fig2.subplot_mosaic(

"""

abc

def

""")

for line, ax in zip(['Ha','Hb','R23','O3','O2','O32'],['a','b','c','d','e','f']):

if line is 'R23' or line is 'O32':

ax2[ax].hist(np.log10(M101Data[line]),bins=50,ec='k')

ax2[ax].set_xlabel(r'$\log({0})$'.format(line))

ax2[ax].set_ylabel(r'$N$')

else:

ax2[ax].hist(np.log10(M101Data[line+'_nored']),bins=50,ec='k')

ax2[ax].set_xlabel(r'$\log(\mathrm{{{0}}})$ [erg s$^{{-1}}$ cm$^{{-2}}$]'.format(line))

ax2[ax].set_ylabel(r'$N$')

We see that our line fluxes are across the same range and are somewhat Gaussian. For context, the H

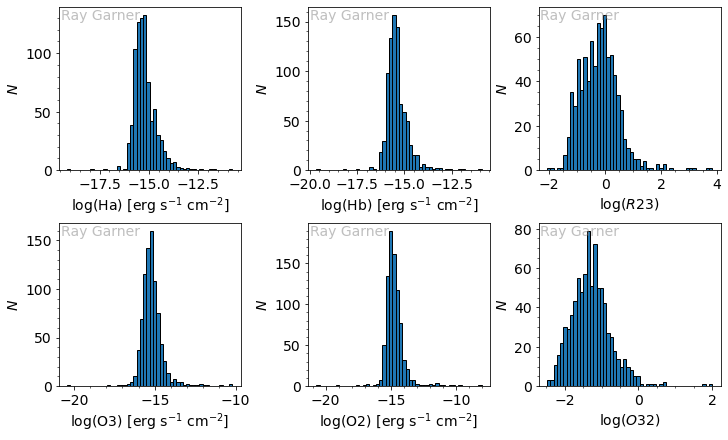

We can also do the same for the associated uncertainties:

fig3 = plt.figure(figsize=(10,6), constrained_layout=True)

ax3 = fig3.subplot_mosaic(

"""

abc

def

""")

for line, ax in zip(['Ha','Hb','R23','O3','O2','O32'],['a','b','c','d','e','f']):

if line is 'R23' or line is 'O32':

ax3[ax].hist(np.log10(M101Data[line+'_err']),bins=50,ec='k')

ax3[ax].set_xlabel(r'$\log({0})$'.format(line))

ax3[ax].set_ylabel(r'$N$')

else:

ax3[ax].hist(np.log10(M101Data[line+'_nored_err']),bins=50,ec='k')

ax3[ax].set_xlabel(r'$\log(\mathrm{{{0}}})$ [erg s$^{{-1}}$ cm$^{{-2}}$]'.format(line))

ax3[ax].set_ylabel(r'$N$')

We see that our O3 and O2 errors are roughly Gaussian, while our H

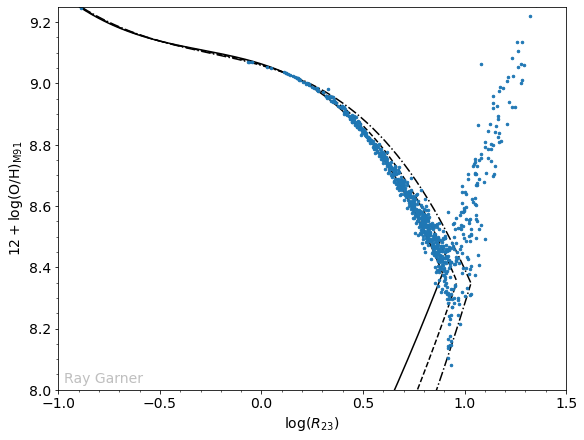

Now we can plot our

However, due to the placement of our narrowband filters, we have no way of measuring the [NII] line emission. Therefore, at the suggestion of Kewley & Dopita (2002), we use the calibration of Zaritsky et al. (1994; Z94), which does not require an upper/lower branch distinction to be made, to calculate an initial guess of the metallicity. This step is problematic for many reasons:

- the Z94 calibration is itself an average of three older theoretical calibrations and will suffer from the same uncertainties in those calibrations;

- the Z94 calibration will be very inaccurate at low abundances (

- the Z94 calibration will preferentially assign most of the

These problems notwithstanding, we will go ahead and use the Z94 calibration to make our initial guesses as to which branch each HII region belongs.

def zaritsky94(log_R23):

return 9.265 - 0.33*log_R23 - 0.202*log_R23**2 - 0.207*log_R23**3 - 0.333*log_R23**4

def mcgaugh91(logR23,logO32,Z_guess):

if Z_guess <= 8.4:

return 12 - 4.944 + 0.767*logR23 + 0.602*logR23**2 - logO32*(0.29 + 0.332*logR23 - 0.331*logR23**2)

elif Z_guess > 8.4:

return 12 - 2.939 - 0.2*logR23 - 0.237*logR23**2 - 0.305*logR23**3 - 0.0283*logR23**4 - logO32*(0.0047 - 0.0221*logR23 - 0.102*logR23**2 - 0.0817*logR23**3 - 0.00717*logR23**4)

Z_guess = zaritsky94(np.log10(M101Data['R23']))

Z_real = np.zeros(0)

for i in range(0,len(M101Data)):

Z = mcgaugh91(np.log10(M101Data[i]['R23']),np.log10(M101Data[i]['O32']),Z_guess[i])

Z_real = np.append(Z_real,Z)

fig4 = plt.figure(figsize=(8,6), constrained_layout=True)

ax4 = plt.subplot(111)

O32_vals = [-.5, 0, 0.5]

R23_vals = np.arange(-1.0,1.3,0.01)

z_vals = np.arange(6.5,9.5,0.01)

for j,ls in zip(O32_vals,['-','--','-.']):

idx = np.argwhere(np.diff(np.sign(mcgaugh91_up(R23_vals,j) - mcgaugh91_dw(R23_vals,j)))).flatten()

ax4.plot(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]], mcgaugh91_up(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]],j), 'k', ls=ls)

ax4.plot(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]], mcgaugh91_dw(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]],j), 'k', ls=ls)

ax4.plot(np.log10(M101Data['R23']), Z_real, color='C0', marker='.', markersize=5, ls='None')

ax4.set_xlabel(r'$\log(R_{23})$')

ax4.set_ylabel(r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{O/H})_{\mathrm{M91}}$')

ax4.set_xlim(-1,1.5)

ax4.set_ylim(8.0,9.25)

Once again, we have the

Normally, we would toss these high

We need to set up a few things first: the number of trials and the combined set of best-fit parameters for all the model parameters (initially empty).

n = 500

m101_z_up = np.array([]) # an array for the upper branch metallicities

m101_z_dw = np.array([]) # an array for the lower (down) branch metallicities

Now we do the simulations. Each time we need to generate the data as well as pass it through the calibrations, one solution for the upper branch and one solution for the lower branch.

for i in range(n):

Hb_trial = np.random.normal(M101Data['Hb_nored'],np.abs(M101Data['Hb_nored_err']))

O2_trial = np.random.normal(M101Data['O2_nored'],np.abs(M101Data['O2_nored_err']))

O3_trial = np.random.normal(M101Data['O3_nored'],np.abs(M101Data['O3_nored_err']))

O32_trial = np.log10(O3_trial/O2_trial)

R23_trial = np.log10((O3_trial + O2_trial)/Hb_trial)

# We use a try/except clause to catch weird regions

try:

up = mcgaugh91_up(R23_trial,O32_trial)

except:

dumdum = 1

continue

try:

dw = mcgaugh91_dw(R23_trial,O32_trial)

except:

dumdum = 1

continue

# Stack the trial onto the running sample

if np.size(m101_z_up) < 1:

m101_z_up = np.copy(up)

else:

m101_z_up = np.vstack((m101_z_up, up))

if np.size(m101_z_dw) < 1:

m101_z_dw = np.copy(dw)

else:

m101_z_dw = np.vstack((m101_z_dw, dw))

A few points to note:

- The routine might not always work. A more sophisticated analysis would catch those errors. Here, I’m using Python’s “try/except” clause to ignore the bad cases.

- In this example, I am starting with an empty array and then stacking on the fit-values only if the fitting routine ran without failing. The “continue” statement stops the routine from dumbly stacking on the last fit-value if the fit failed. I do things this way so that the fitpars array is always the correct size to match the number of correctly-run trials.

- I am picking random values surrounding each region’s values within its uncertainties, assuming a Gaussian distribution within those uncertainties. That may not necessarily be the case, but it will work for our purposes.

Having done all that, let’s look at the size of the set of trials:

print(m101_z_up.shape)

print(m101_z_dw.shape)

(500, 849)

(500, 849)

This shows that all of our 500 trials were successful! Now let’s take a look at the distribution:

print('Upper Branch Metallicity: {:.2f} +/- {:.2f}'.format(np.nanmedian(m101_z_up),np.nanstd(m101_z_up)))

print('Lower Branch Metallicity: {:.2f} +/- {:.2f}'.format(np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw),np.nanstd(m101_z_dw)))

Upper Branch Metallicity: 8.54 +/- 1.35

Lower Branch Metallicity: 8.15 +/- 0.55

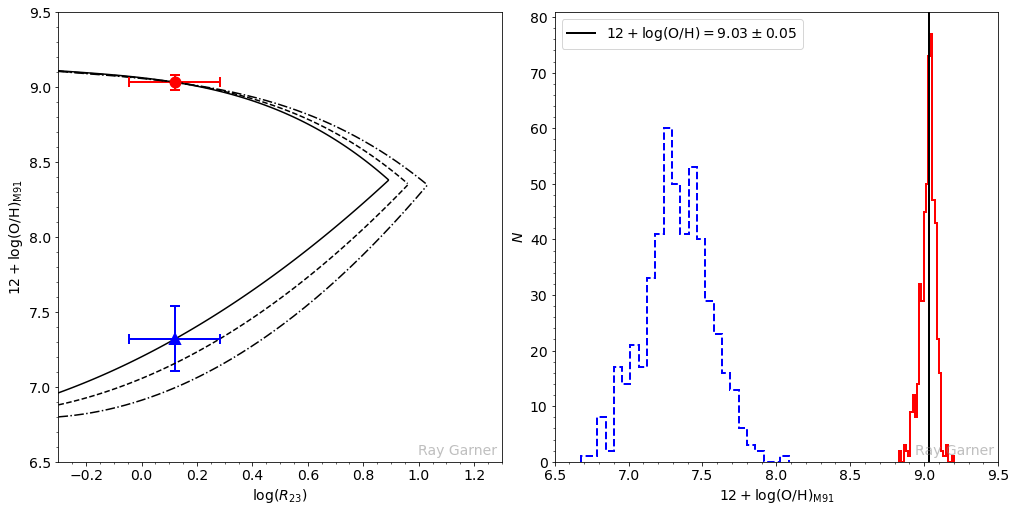

Now comes the method outlined by Moustakas et al. (2010). You can imagine that there are three possible cases when you look at a particular HII region’s upper and lower branch solutions. In the first case, the upper and lower branch solutions are distinct and well-separated, i.e., they are outside of each other’s uncertainties. Once the appropriate branch has been chosen, the corresponding metallicity follows. This is easily seen in the left-hand plot below: the upper branch solution (red circle) is above and well-separated from the lower branch solution (blue triangle). The right-hand plot below shows the Monte Carlo distribution of

i = 3

fig5 = plt.figure(figsize=(14,7), constrained_layout=True)

ax5 = fig5.subplot_mosaic(

"""

ab

""")

# Plot the M91 calibration for particular O32 values

O32_vals = [-.5, 0, 0.5]

R23_vals = np.arange(-0.3,1.3,0.01)

z_vals = np.arange(6.5,9.5,0.01)

for j,ls in zip(O32_vals,['-','--','-.']):

idx = np.argwhere(np.diff(np.sign(mcgaugh91_up(R23_vals,j) - mcgaugh91_dw(R23_vals,j)))).flatten()

ax5['a'].plot(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]], mcgaugh91_up(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]],j), 'k', ls=ls)

ax5['a'].plot(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]], mcgaugh91_dw(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]],j), 'k', ls=ls)

# Plot the upper branch solution

ax5['a'].errorbar(np.log10(M101Data[i]['R23']), np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]),

xerr = (0.434*M101Data[i]['R23_err'])/M101Data[i]['R23'],

yerr = np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]), mec='r', mfc='r', marker='o', markersize=10, ecolor='r', elinewidth=2,

capsize = 5, mew=2)

# Plot the lower branch solution

ax5['a'].errorbar(np.log10(M101Data[i]['R23']), np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]),

xerr = (0.434*M101Data[i]['R23_err'])/M101Data[i]['R23'],

yerr = np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i]), mec='b', mfc='b', marker='^', markersize=10, ecolor='b', elinewidth=2,

capsize = 5, mew=2)

# Plot the upper and lower branch histograms

ax5['b'].hist(m101_z_up[:,i], bins=25, histtype='step', color='r', ls='-', lw=2)

ax5['b'].hist(m101_z_dw[:,i], bins=25, histtype='step', color='b', ls='--', lw=2)

# Set plot kwargs

ax5['a'].set_xlabel(r'$\log(R_{23})$')

ax5['a'].set_ylabel(r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{O}/\mathrm{H})_{\mathrm{M91}}$')

ax5['b'].set_xlabel(r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{O}/\mathrm{H})_{\mathrm{M91}}$')

ax5['b'].set_ylabel(r'$N$')

ax5['a'].set_xlim(-0.3,1.3)

ax5['a'].set_ylim(6.5,9.5)

ax5['b'].set_xlim(6.5,9.5)

# If upper branch solution is above lower branch solution

if np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]) > np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]):

# If they aren't well-separated, i.e., within each other's 1*sigma

if (np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]) - np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]) < np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i])) and (np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]) + np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i]) > np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i])):

(mu1, sig1) = norm.fit(m101_z_up[:,i][~np.isnan(m101_z_up[:,i])])

(mu2, sig2) = norm.fit(m101_z_dw[:,i][~np.isnan(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

avg = np.nanmean([np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]), np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

sig = np.nanmedian([np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]),np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

ax5['b'].axvline(avg, color='k', ls='-', lw=2, label=r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{{O}}/\mathrm{{H}}) = {:.2f} \pm {:.2f}$'.format(avg,sig))

ax5['b'].legend(loc='best')

# If they are well-separated, let the initial guess decide which branch to use

else:

if Z_guess[i] <= 8.4:

ax5['b'].axvline(np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]), color='k', ls='-', lw=2, label=r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{{O}}/\mathrm{{H}}) = {:.2f} \pm {:.2f}$'.format(np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]),np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i])))

ax5['b'].legend(loc='best')

else:

ax5['b'].axvline(np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]), color='k', ls='-', lw=2, label=r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{{O}}/\mathrm{{H}}) = {:.2f} \pm {:.2f}$'.format(np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]),np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i])))

ax5['b'].legend(loc='best')

# If upper branch solution is below lower branch solution

elif np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]) < np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]):

# If they aren't well-separated, i.e., within each other's 1*sigma

if (np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]) + np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]) > np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i])) and (np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]) - np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i]) < np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i])):

(mu1, sig1) = norm.fit(m101_z_up[:,i][~np.isnan(m101_z_up[:,i])])

(mu2, sig2) = norm.fit(m101_z_dw[:,i][~np.isnan(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

avg = np.nanmean([np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]), np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

sig = np.nanmedian([np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]),np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

ax5['b'].axvline(avg, color='k', ls='-', lw=2, label=r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{{O}}/\mathrm{{H}}) = {:.2f} \pm {:.2f}$'.format(avg,sig))

ax5['b'].legend(loc='best')

# If they are well-separated, mark it as indeterminant

else:

ax5['b'].text(0.05,0.9,'No determination possible', ha='left', va='center', transform=ax5['b'].transAxes)

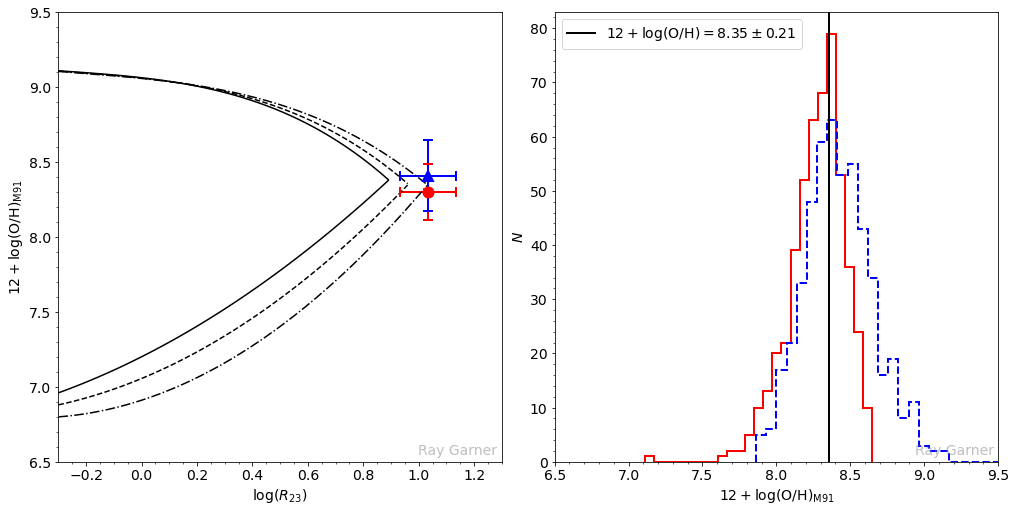

In the second case, the formal solution on the lower branch is larger than the solution on the upper branch (note that the blue triangle is now above the red circle in the plot on the left below). In the right plot below, the overlapping region of the histograms corresponds to values of

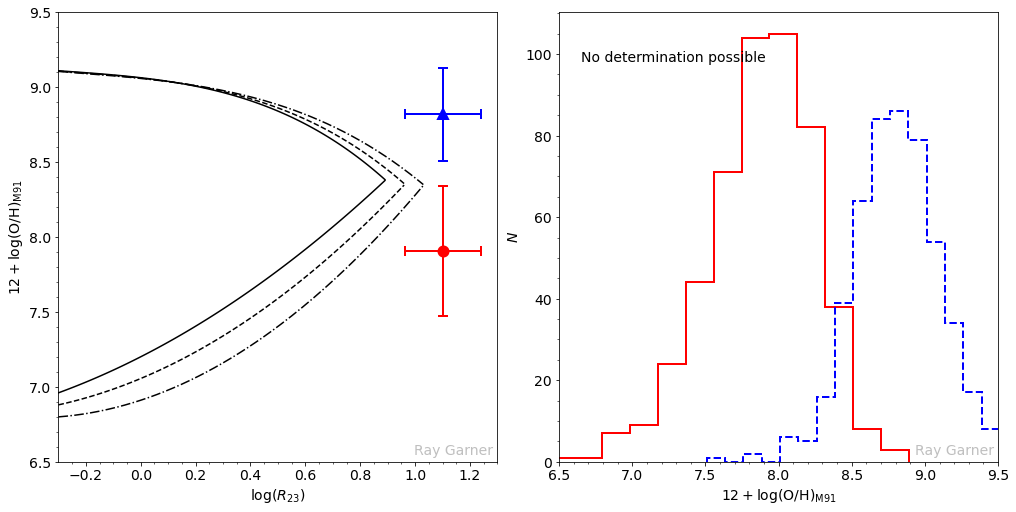

Finally, the third case is where no oxygen abundance measurement is possible using the M91 calibration. Here, the upper and lower branch solutions are statistically inconsistent with each other, given the measurement uncertainties; therefore no solution exists, and these objects must be rejected.

Now, we can write a code that doesn’t just plot this, but saves the determined (or undetermined) value for each region as a new column in our DataFrame.

M91 = np.zeros(0)

M91_err = np.zeros(0)

Z_guess = zaritsky94(np.log10(M101Data['R23']))

for i in range(0,len(M101Data)):

if np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]) > np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]):

if (np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]) - np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]) < np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i])) and (np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]) + np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i]) > np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i])):

(mu1, sig1) = norm.fit(m101_z_up[:,i][~np.isnan(m101_z_up[:,i])])

(mu2, sig2) = norm.fit(m101_z_dw[:,i][~np.isnan(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

avg = np.nanmean([np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]), np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

sig = np.nanmedian([np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]),np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

M91 = np.append(M91,avg)

M91_err = np.append(M91_err,sig)

else:

if Z_guess[i] <= 8.4:

M91 = np.append(M91,np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]))

M91_err = np.append(M91_err,np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i]))

else:

M91 = np.append(M91,np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]))

M91_err = np.append(M91_err,np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]))

elif np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]) < np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]):

if (np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]) + np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]) > np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i])) and (np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i]) - np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i]) < np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i])):

(mu1, sig1) = norm.fit(m101_z_up[:,i][~np.isnan(m101_z_up[:,i])])

(mu2, sig2) = norm.fit(m101_z_dw[:,i][~np.isnan(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

avg = np.nanmean([np.nanmedian(m101_z_up[:,i]), np.nanmedian(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

sig = np.nanmedian([np.nanstd(m101_z_up[:,i]),np.nanstd(m101_z_dw[:,i])])

M91 = np.append(M91,avg)

M91_err = np.append(M91_err,sig)

else:

M91 = np.append(M91,np.nan)

M91_err = np.append(M91_err,np.nan)

else:

M91 = np.append(M91, np.nan)

M91_err = np.append(M91_err, np.nan)

M101Data['M91'] = M91

M101Data['M91_err'] = M91_err

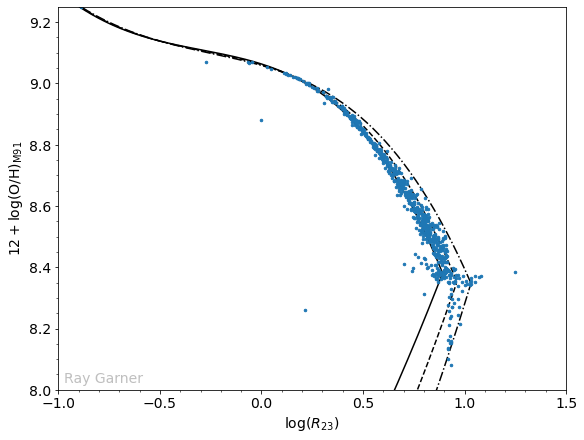

Let’s take a look at the

fig4 = plt.figure(figsize=(8,6), constrained_layout=True)

ax4 = plt.subplot(111)

O32_vals = [-.5, 0, 0.5]

R23_vals = np.arange(-1.0,1.3,0.01)

z_vals = np.arange(6.5,9.5,0.01)

for j,ls in zip(O32_vals,['-','--','-.']):

idx = np.argwhere(np.diff(np.sign(mcgaugh91_up(R23_vals,j) - mcgaugh91_dw(R23_vals,j)))).flatten()

ax4.plot(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]], mcgaugh91_up(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]],j), 'k', ls=ls)

ax4.plot(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]], mcgaugh91_dw(R23_vals[R23_vals <= R23_vals[idx]],j), 'k', ls=ls)

ax4.plot(np.log10(M101Data['R23']), M101Data['M91'], color='C0', marker='.', markersize=5, ls='None')

ax4.set_xlabel(r'$\log(R_{23})$')

ax4.set_ylabel(r'$12 + \log(\mathrm{O/H})_{\mathrm{M91}}$')

ax4.set_xlim(-1,1.5)

ax4.set_ylim(8.0,9.25)

Comparing this plot to the one we made before, we have now removed the “unphysical” regions that did not fall on the calibration even within their uncertainties. There are four outliers which will require further investigation to determine whether they are realistic or not. Another feature we notice now is a line of points at about

Conclusions

Using Monte Carlo and the methodology outlined by Moustakas et al. (2010), I have hopefully illustrated its usefulness in robustly determining metallicities. This method allows for a straightforward calculation of realistic uncertainties on the abundance as determined by strong-line methods. Obviously, this method will still suffer from the known problems associated with strong-line abundance determinations, but we will be able to state our uncertainties in a more statistical sense. Additionally, although not illustrated here, this can be applied to any strong-line calibration using the

As always, let me know if you spot any errors in my code or the logic behind this method!